Pinebook Pro

Impressive hardware that gives a glimpse of a bright future

| 20 min readI recently got my hands on a Pinebook Pro from PINE64, and have spent the past couple of weeks using it—admittedly in rotation with a Dell Precision 5530, Slimbook Pro X, and System76 Meerkat. I have thoughts. tl;dr: Pinebook Pro is an impressive piece of hardware that provides a glimpse into an even brighter future of Linux-toting hardware.

Photo by Daniel Foré

Who is PINE64?

PINE64 is a both a global community and a brand of hardware devices featuring ARM processors. Many of the devices are single-board computers—similar to a Raspberry Pi—for tinkering, hacking, and special-purpose commercial/industrial applications. PINE64 caught the attention of the Linux desktop community when they announced the Pinebook: an inexpensive laptop featuring an ARM processor on a PINE64 main board. They followed that up with the Pinebook Pro, a higher-end and faster laptop that’s still incredibly affordable and often touted as an alternative to cheap Chromebooks that folks buy just to use with desktop Linux.

PINE64 is also shipping the PinePhone, a smartphone designed to run various Linux-based OSes, and working on PineTime, a smartwatch platform in its early stages.

The unique thing about PINE64 is that they are very open, and work closely with several different open source communities to encourage and enable the porting of OSes to their hardware. This can mean sending devices to maintainers (like with elementary), or it can mean special runs of hardware like the PinePhone UBPorts Community Edition, with which PINE64 donated $10 of each purchase to UBPorts. It also means an expansive wiki with all sorts of information about running different software, tweaking firmware, and even doing hardware modifications or upgrades.

It even means that every part of the Pinebook Pro can be purchased individually from PINE64! So if you break something or want a spare, it’s extremely easy to repair it yourself—which is huge. Consequently, Pinebook Pro is the perfect Right to Repair laptop.

About elementary OS on Pinebook Pro

Getting this out of the way since I know it will be what a lot of folks are interested in: elementary OS on Pinebook Pro is usable, but not what I would consider an experience that we would sign off on. We recommend a modern Intel Core i3 or better processor for a reason, and while many tout elementary OS as lightweight and great for lower-powered devices, that has never been a target for us. It’s just not optimized for this class of hardware; animations are choppy, apps are slower than we’d like, and even lightweight web browsing can chug quite a bit on this hardware with elementary OS.

As such, I would not currently recommend purchasing a Pinebook Pro as a primary device to run elementary OS. That said, there is some ongoing work towards experimental builds of elementary OS for Pinebook Pro if you happen to be a fan and already have a Pinebook Pro sitting around to toy with. I’ll share more either here or on the elementary blog once things are farther along.

Hardware

Let’s dive right into it: Pinebook Pro is a well-designed laptop, and downright impressive at this price point. PINE64 sells the Pinebook Pro for $200 USD, but there is a caveat when comparing to other devices in this price range: PINE64 has noted that they sell the Pinebook Pro at or near cost. While margins on computers tend to be thin, I suspect this exact laptop would cost significantly more if it were sold through almost anyone else—especially since they’re not subsidizing the cost with preloaded software, a subscription, etc.

Still, it’s $200 for end users, and PINE64 seems to have made the right decisions to get it to that price point.

The big difference from most laptops is the processor: it’s an ARM-based Rockchip RK3399 system-on-a-chip which includes two 2.0 GHz ARM Cortex-A72 cores and four lower-power 1.5 GHz ARM Cortex-A53 cores—along with a Mali T860 MP4 GPU. Technobabble aside, this means the brains are more similar to what you’d find in a high-end Raspberry Pi or a smartphone—the processors and GPU on display here are lower-powered than than the Intel or AMD processors you’d typically find in a laptop, which has its pros and cons.

On the plus side, the processors draw much less power over all than most laptops. This means better battery life, and even enables a completely fanless design. Consequently, the laptop is silent while easily lasting through an entire day’s worth of work. The lower power draw also means the laptop can charge off a USB-C phone charger, or even a portable battery typically advertised for topping off your phone or tablet.

On the other hand, the lower performance of the processor and graphics definitely shows through, especially when running a full desktop software stack (like elementary OS). While general usage inside of a native app or two might feel great, multitasking slows things down a bit. Non-GPU-accelerated animations definitely suffer—though that’s more of a software optimization issue, and CPU-intensive tasks like exporting graphics or compiling large software definitely take a hit.

More on the experience of using it in a bit, though—let’s move on to more hardware.

Design & feel

I doubt anyone would be able to tell this laptop costs a fraction of high-end laptops based on its design and feel. The black magnesium-alloy lid and bottom give off a high-end feel from the very first touch. The entire laptop is rigid and feels like one solid piece, even if the sides, keyboard deck, and palm rest are actually some sort of single-piece molded plastic. There is very minimal flex over all, likely thanks to that rigid magnesium alloy acting as a sort of exoskeleton.

The design over all is minimal. It’s all-black, with absolutely no logos or embellishments on the chassis. Four rubber feet at the corners keep the Pinebook Pro from sliding around, and provide a tiny bit of an air gap from the bottom metal of the chassis.

I love the look. One critique is that as sleek as the matte black finish is, the back of the display is a fingerprint magnet; I feel like I have to wipe the thing down daily so I don’t look like some sort of greasy animal. Another critique is that the fanless design plus the metal bottom acting a a heat sink means that the bottom of the laptop can get really hot—uncomfortably and maybe even dangerously so at times. It’s fine when using on a desk, but actually putting it on your lap for long periods of time while stressing the processor becomes worrisome.

Display

The display is impressive for this class of laptop. It’s an IPS panel, and the colors look accurate to my eye. It’s not washed out at all, and viewing angles are good. It does seem to get a bit dimmer at significant off-center angles than I’d love, but it’s nothing that affects my daily usage. It also gets reasonably bright—as bright as I’ve ever needed it.

My one complaint is actually the resolution, but perhaps not in the way you’d expect—unless you listen to my regular rants on social media, in which case: no, the horse is not dead and I will continue to beat it.

The resolution is maybe just a bit too high. At 14”, the 1920×1080 resolution means that text and the mouse cursor are just a bit too small for my liking. Some folks might be fine with it, and it’s definitely something you can get used to. But if you’re coming from regularly using a 15.6″ display with the same logical resolution (3840×2160, or 1920×1080@2x) or a 13.3″ display with a lower logical resolution (e.g. 3200×1800 or 1600×900@2x), it just makes the text and UI seem extra small.

Normally, I’d argue that the manufacturer could have gone for a higher resolution like 3200×1800 (1600×900@2x) for HiDPI. Or maybe with 3840×2160 (exactly twice this resolution), the smaller text would be more bearable since it would at least be more crisp. But I’m certain trying to go for HiDPI would just exasperate the already-limited processing and graphical resources on this hardware.

Lucky for me, an unreleased experimental feature for elementary OS is UI scaling based on text size, and it seems to be working pretty well. I’ve bumped the size to “Large”, and everything is much more readable at a comfortable distance. At least I have a good excuse to dogfood this now?

Keyboard & trackpad

The keyboard definitely continues the “impressive, especially at this price point” trend of the Pinebook Pro. I opted for the ANSI (US layout) model, and the layout is perfect in my opinion. Keys feel like the perfect size, and everything is right where I’d expect it. Travel-wise, the keys have a decent amount of travel and a little of a click sound. I really like the amount of travel, and my only critique is that some keys don’t feel like they travel perfectly vertically; especially the arrow keys due to their smaller size.

I also appreciate the PINE64-branded Super or ⌘ key. It’s cute, and since it’s the only branding on the whole machine, it works well.

The one big omission here is a keyboard backlight. It’s absolutely understandable, but I didn’t realize how often I did rely on that for hitting some less-used keys or Fn-key combinations in low light situations. My only other critique is with the Function keys: like the Slimbook Pro X, the F1–F12 keys default to their less-used F1–F12 functions, and require an extra Fn modifier to access things like brightness and volume. I’d prefer those media keys default to their media controls and require Fn to access the F1–F12 functions, or at least a function lock in hardware or software to allow that change.

Day-to-day usage

In practice, I was able to do quite a bit of lightweight desktop and web development on the Pinebook Pro with few issues. In fact, this entire blog post was written and published on the Pinebook Pro, and I used the hardware for all elementary development for a week. Issue triage, code reviews, and feature development actually went fine. Compiling elementary apps may have taken a bit longer than I’m used to, but not so much that it hindered me while doing my work. And all of the apps compile and run perfectly fine on this architecture, which is awesome.

Having multiple browsers open e.g. while doing web development plus researching something would slow things down a bit as well, and some heavier web apps were barely usable—Slack, in particular, was painful, as was BigBlueButton (the web-based conferencing software used by GUADEC). Exporting high-resolution images from Glimpse—something I’m used to taking just a few seconds on my much, much more powerful Dell Precision—would sometimes take a minute or more. If anything, this hardware lets you know when something is a CPU-bound operation.

I was impressed over all with just how usable it was, though; I’ve attempted to use Raspberry Pi boards as desktop computers, and it just never felt worthwhile to me. Maybe it’s because the Pinebook Pro has a great display, keyboard, trackpad, and fast storage all in one package, but it actually feels like a “real computer.” Just one that’s on the slightly slower side. With dedicated software optimization and a more user-friendly out-of-the-box experience, I would be tempted to recommend Pinebook Pro to folks over a Chromebook—and definitely over a Windows laptop in this price range. And if you’re a Linux-loving tinkerer, then it’s a great deal as-is today.

Out of the box experience

PINE64 provided this Pinebook Pro to me explicitly for elementary work, so I didn’t expect to keep the default software around long. However, it’s worth covering in case you’re considering purchasing a Pinebook Pro.

Out of the box, the Pinebook Pro currently ships with Manjaro Linux. That’s an… interesting choice to me. It seems like the reasoning is that Manjaro is the most optimized for the hardware right now, with support for all hardware and GPU acceleration of the user interface by default. If you’re an existing Manjaro user, this is probably an awesome choice for you—and I do have to applaud the efforts of the Manjaro and KDE teams for making everything work well on this hardware.

However, I have thoughts about Manjaro and the KDE Plasma UI. To me, the combination of Manjaro and KDE Plasma feel like they exhibited everything that non-Linux-users point out when complaining about Linux. On first boot, I landed in a white and green on black terminal-based UI, asking me to set up a user name, set a hostname, and add my user to certain user groups. It felt extremely Linux, and not in a good way. After that, there was a pretty boot screen and then the KDE greeter and UI. The default configuration of KDE used a dark mode, which also felt unnecessarily “Linux”. I think folks should have the option of a dark style, but defaulting to it without offering a preference felt like an odd choice.

Now, thanks to the design of KDE Plasma, almost everything about the user interface—including the visual style—can be changed. However, I don’t think that’s necessarily the best thing. Of course, I’m a UX architect at elementary and my opinions reflect the philosophies of elementary OS—but there is just too much going on in KDE Plasma. It feels more like a massive compilation of tools with which to build your own OS instead of an opinionated, thought-through experience. At the same time, even with all this built-in configuration and flexibility, some things were difficult to find or configure. For example, I couldn’t find how to change the wallpaper in the system settings, and even using the universal search returned nothing useful. Apparently, you have to access a separate settings app from the overcrowded context menu on the desktop in order to change the wallpaper. This sort of experience was echoed several times when I wanted to change a few basic settings: there was so much going on combined with a subpar search that I would often give up before I found what I wanted.

On the Manjaro side, things were mostly fine albeit unfamiliar to me coming from the Debian world of Raspberry Pi OS, Ubuntu, and elementary OS. The package manager felt old-school, with most packages lacking non-technical descriptions and screenshots. Installing an app or updates felt like an overly-technical affair with jargon-filled dialogs and logs asking the user to make decisions they might not know the answer to, or even be qualified to decide. I suppose some gatekeeping Arch Linux users might think that the administrator of a computer should be knowledgeable about complex system internals, but I just don’t agree there—I’ve been a Linux user for half my life now, and I still found it too complex. I’d hate to give this to someone as their first impression of a Linux-based OS.

If you are super into Linux internals and want your operating system to be a bucket of LEGOs, I suppose Manjaro and KDE Plasma could be awesome, and I would encourage you to give them a try. But I much prefer an opinionated design of something like GNOME or elementary OS over this.

My adventures getting elementary OS on Pinebook Pro

I’m not going to dive into all of the behind-the-scenes of elementary OS images—hopefully David Hewitt, Daniel Foré, and I can figure out how best to share this later on. But I do want to share some anecdotes about getting elementary software to run on the Pinebook Pro, and maybe some things to avoid.

First, it’s possible to boot alternative operating systems off of the microSD card which is awesome! Performance takes a bit of a hit due to the slower storage (and the fastest microSD card you can fine is highly recommended), but it makes it easy to try out builds of Chromium OS, Android, Debian, Ubuntu, etc. without committing and with low risk of soft-bricking your hardware—something I got some experience with.

I started my journey to play with elementary software on the Pinebook Pro by trying to install and compile Pantheon (our desktop environment) and elementary apps on Manjaro. Much of it installed easily out of the box thanks to efforts from the Manjaro community to port Pantheon, but it seemed some components were a bit out of date or missing altogether for the ARM64 architecture. After my adventures there left me booting to the text-based TTY instead of a graphical login screen, I decided to try out some other OSes.

I found an Ubuntu 20.04 image that was designed to work off the microSD card, and got started with it. The GNOME desktop environment was much more familiar than KDE Plasma, so I poked at it for a bit before getting started with Pantheon. I then added the various elementary PPAs and packages, and uninstalled most of the Ubuntu and GNOME things that don’t come with elementary OS. The result was a functional though a bit buggy facsimile of an unstable build of elementary OS 6. I suspected the microSD card was partially at fault for some of the performance issues I was seeing, so I decided to investigate how to get it running off the eMMC next.

After I tweeted about it, Lukasz Erecinski shared a way to get it onto the eMMC which worked, but led to some issues. Apparently, something with the bootloader in the hacked together Ubuntu-to-elementary-OS build didn’t actually tell the LCD to come on, meaning it was successfully booting to the eMMC, but I couldn’t see anything.

At first we thought the bootloader on the eMMC was toast altogether; this lead me to open up the Pinebook Pro to flip the internal eMMC switch, which would cause the Pinebook Pro to boot to the microSD card instead. This worked, but we still wanted to be able to boot to the eMMC. We re-enabled the eMMC and used the USB to serial adapter (which PINE64 thankfully included in the packaging for me!) to watch the boot process. The U-Boot bootloader outputs over serial, and then I was presented with a TTY login to the install on the eMMC. From here, we managed to wipe out the eMMC bootloader to force it to boot back to the microSD card while keeping the eMMC mounted. From the microSD TTY, we flashed a known-good experimental elementary OS image (that David Hewitt had been working on) back to the eMMC. I rebooted, and the Pinebook Pro booted into it! I put everything back together, and have been running that image ever since.

So, just be sure to not flash the eMMC unless you know it’s an image made to be flashed to the eMMC—and if you do mess something up, know that you can flip that eMMC switch to boot to the microSD card and use the USB-to-serial adapter to debug.

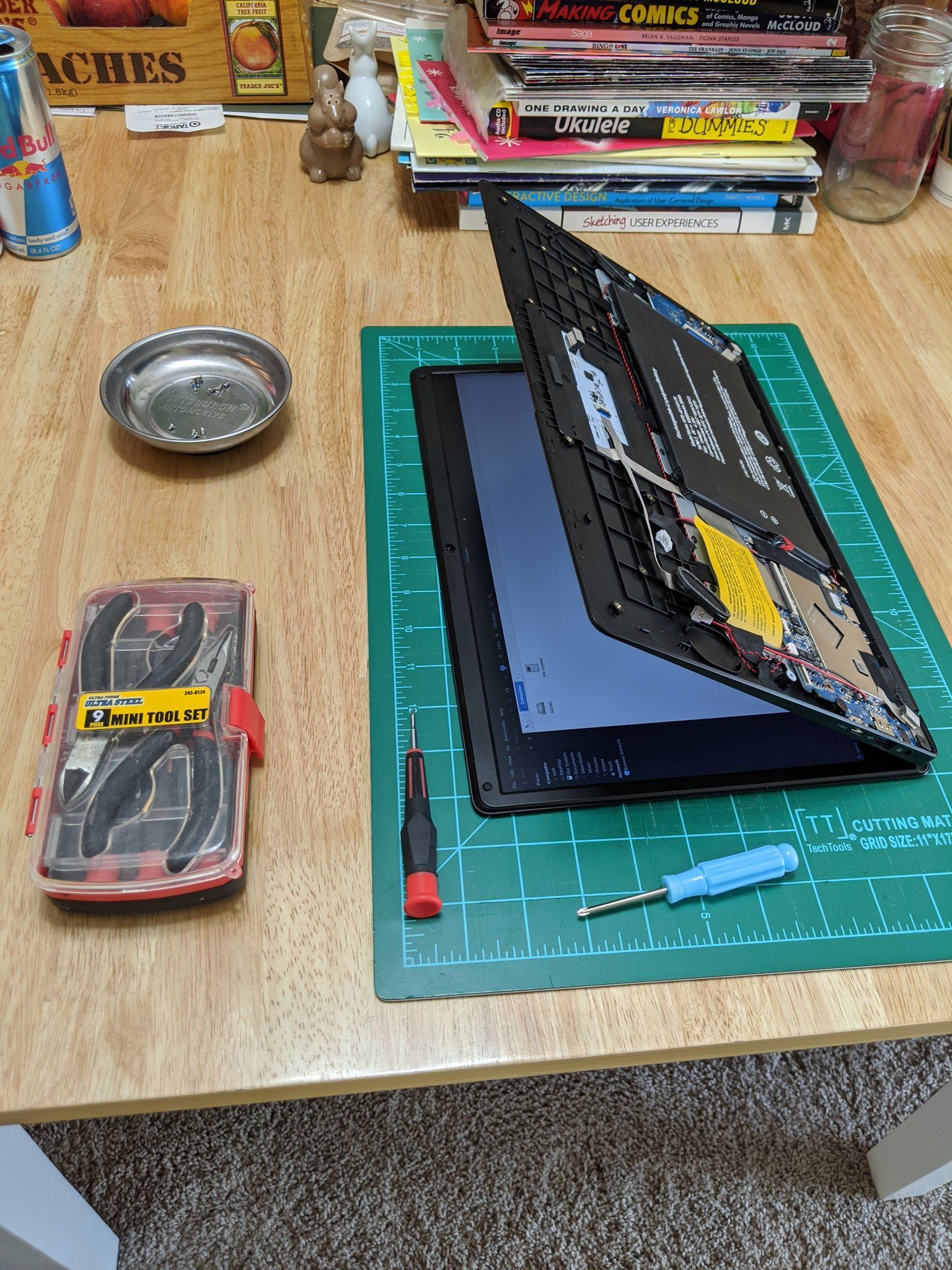

Disassembly and re-assembly

Since I got some experience taking the Pinebook Pro apart and re-assembling it, I might as well share my thoughts. It was a breeze! I saw a bunch of warnings about it seeming fragile, so sharp that you could cut yourself, and hard to re-assemble, but honestly I didn’t have any issues. To be fair, I’ve done a number of small electronics repairs and opened up quite a few laptops from various manufacturers, but the Pinebook Pro was among the easiest to pop open: just ten screws on the bottom panel, then it popped off. The only slightly tricky part was that the speakers are adhered to that bottom panel and have thin wires, but they popped off easily enough.

There are two switches on the inside: one is a power cut-off for the eMMC module (useful for recovering from eMMC bootloader issues!), and the other switches the headphone jack over to work with the USB to serial adapter.

Re-assembling was easy enough as well: just disassembly in reverse. All the screw posts lined up perfectly, and I re-attached the bottom panel without incident.

Wrap up… and the future

Over all, I want to stress how impressed I am with Pinebook Pro. The hardware looks and feels like something far above its price point, and it’s an excellent Linux tinker kit right now. With some more software work and improved thermals, I think it would have a chance at being an excellent mainstream but “budget” Linux machine.

What’s more interesting to me, however, is what this means for the future of Linux hardware. We’ve seen Android devices, Chromebooks, and some Windows machines adopt ARM-based processors, but it’s never been a general-purpose platform like Intel architecture. Now with Apple planning to transition to their own proprietary ARM-based processors across all of their computers, it has caused some people to look more closely at ARM.

Platforms like Pinebook Pro and its SOC make me hopeful for additional open-source-friendly ARM hardware in the future, and Linux-based OSes are uniquely positioned to take advantage of them. With an open source stack and a completely open source collection of native apps like we have with elementary AppCenter, we can trivially recompile the entire operating system and ecosystem for these new processors—and they run great already. Proprietary apps and legacy apps from other platforms will take a lot more effort to port or virtualize, so we should take this head start and make it count.

I think that’s it! Did I miss anything? Hit me up on social media or via email, conveniently all linked below.